How can we improve temperature measurements for stars?

Most FGK-type stars have effective temperature measurements accurate to only 200-300K, with none besides the Sun being more accurate than 50K (Jofré et al., 2019). For exoplanet host stars, there is a 2% uncertainty floor on temperature, equating to roughly 120K on a G0-type star (Tayar et al. 2022). These widespread systematic uncertainties and inconsistencies on temperature are not trivial: a shift of ±75K in for main-sequence stars can lead to an underestimation of asteroseismic ZAMS/TAMS ages of up to 0.4-0.6 Gyr (Valle et al., 2018), and systematic trends in stellar parameters can lead to spurious trends in population studies of exoplanet host stars and for Galactic archaeology.

Along with my PhD supervisor Dr. Pierre Maxted, I developed a novel method to address the problem of stellar effective temperatures using observations of detached eclipsing binary systems. The method, described in detail in my first paper (Miller et al., 2020), is based on the definition of effective, reformulated in terms of angular diameter and bolometric flux:

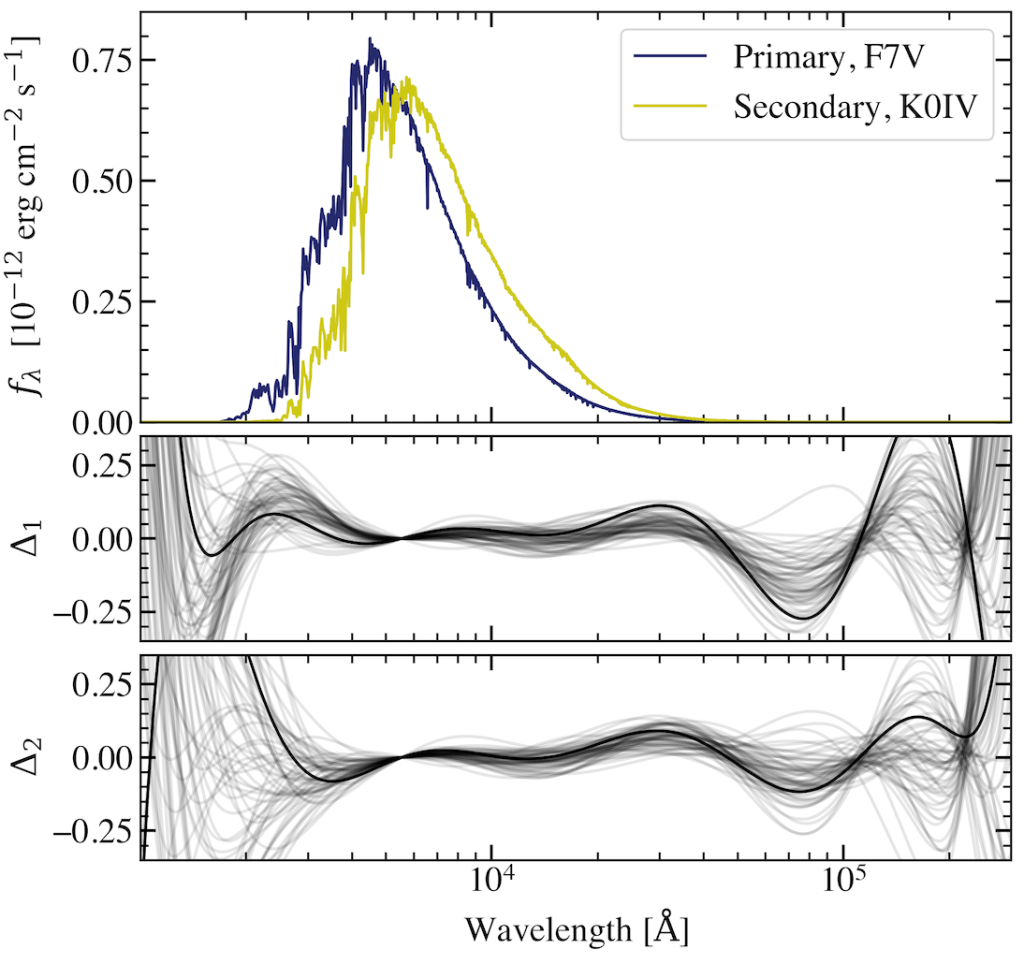

The observational data used to determine the angular diameters consist of high-quality light curves from TESS or Kepler, plus parallax from Gaia and/or independent astrometric orbits. The bolometric flux is inferred from absolute magnitudes across near-UV, visible and near-IR wavelengths, and binary flux ratios measured from a set of light curves in several photometric bands. A spectral energy distribution (SED) provides the small-scale features for the overall flux integration, but instead of regular SED fitting we employ a different approach to find a balance between the data and the physics. Bolometric flux is only obtainable from band-limited photometric measurements if the SED is known, which requires knowledge of effective temperature; so to break this circular argument, we use Legendre polynomials to distort the model SED for each star and produce the functions that are integrated to predict magnitudes, flux ratios, and hence temperature, after sampling the posterior with the emcee Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampler.